Hi!

If you're looking for new content about user research and usability testing techniques, you probably want to go to usabilitytesting.wordpress.com.

There's a brand new post right now: Ending the opinion wars!

No, really. We'd love it if you followed us over there. Please come!

Dana

Usability Testing

How to plan, design, and conduct effective tests

Monday, August 20, 2012

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

The importance of rehearsing

Sports teams drill endlessly. They walk through plays, they run plays, they practice plays in scrimmages. They tweak and prompt in between drills and practice. And when the game happens, the ball just knows where to go.

This seems like such an obvious thing, but we researchers often poo-poo dry runs and rehearsals. In big studies, it is common to run large pilot studies to get the kinks out of an experiment design before running the experiment with a large number of participants.

But I've been getting the feeling that we general research practitioners are afraid of rehearsals. One researcher I know told me that he doesn't do dry runs or pilot sessions because he fears that makes it look to his team like he doesn't know what he is doing. Well, guess what. The first "real" session ends up being your rehearsal, whether you like it or not. Because you actually don't know exactly what you're doing -- yet. If it goes well, you were lucky and you have good, valid, reliable data. But if it didn't go well, you just wasted a lot of time and probably some money.

The other thing I hear is that researchers are pressured for time. In an Agile team, for example, everyone feels like they just have to keep moving forward all the time. This is an application development methodology in desperate want of thinking time, of just practicing craft. The person doing the research this week has finite time. The participants are only available at certain times. The window for considering the findings closes soon. So why waste it rehearsing what you want to do in the research session?

Conducting dry runs, practice sessions, pilots, and rehearsals -- call them whatever works in your team -- gives you the superpower of confidence. That confidence gives you focus and relaxation in the session so you can open your mind and perception to what is happening with the user rather than focusing on managing the session. And who doesn't want the super power of control? Or of deep insight? These things don't come without preparation, practice, and poking at improving the protocol.

You can't get that deep insight in situ if you're worried about things like how to transfer the control of the mouse to someone else in a remote session. Or whether the observers are going to say something embarrassing at just the wrong time. Or how you're going to ask that one really important question without leading or priming the participant.

The way to get to be one with the experience of observing the user's experience is to practice the protocol ahead of time.

There are 4 levels of rehearsal that I use. I usually do all of them for every study or usability test.

All this rehearsal? As the moderator of a research session, you're not the star -- the participant is. But if you aren't comfortable with what you're doing and how you're doing it, the participant won't be comfortable and relaxed. either. And you won't get the most out of the session. But after you get into the habit of rehearsing, when it comes game time, you can concentrate on what is happening with the participant. Instead, those rehearsal steps become ways to test the test, rather than testing you.

There's a lot of truth to "practice makes perfect." When it comes to conducting user research sessions, that practice can make all the difference in getting valid data and useful insights. As Yogi Bera said, "In theory, there's no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is."

This seems like such an obvious thing, but we researchers often poo-poo dry runs and rehearsals. In big studies, it is common to run large pilot studies to get the kinks out of an experiment design before running the experiment with a large number of participants.

But I've been getting the feeling that we general research practitioners are afraid of rehearsals. One researcher I know told me that he doesn't do dry runs or pilot sessions because he fears that makes it look to his team like he doesn't know what he is doing. Well, guess what. The first "real" session ends up being your rehearsal, whether you like it or not. Because you actually don't know exactly what you're doing -- yet. If it goes well, you were lucky and you have good, valid, reliable data. But if it didn't go well, you just wasted a lot of time and probably some money.

The other thing I hear is that researchers are pressured for time. In an Agile team, for example, everyone feels like they just have to keep moving forward all the time. This is an application development methodology in desperate want of thinking time, of just practicing craft. The person doing the research this week has finite time. The participants are only available at certain times. The window for considering the findings closes soon. So why waste it rehearsing what you want to do in the research session?

Conducting dry runs, practice sessions, pilots, and rehearsals -- call them whatever works in your team -- gives you the superpower of confidence. That confidence gives you focus and relaxation in the session so you can open your mind and perception to what is happening with the user rather than focusing on managing the session. And who doesn't want the super power of control? Or of deep insight? These things don't come without preparation, practice, and poking at improving the protocol.

You can't get that deep insight in situ if you're worried about things like how to transfer the control of the mouse to someone else in a remote session. Or whether the observers are going to say something embarrassing at just the wrong time. Or how you're going to ask that one really important question without leading or priming the participant.

The way to get to be one with the experience of observing the user's experience is to practice the protocol ahead of time.

There are 4 levels of rehearsal that I use. I usually do all of them for every study or usability test.

- Script read-through. You've written the script, probably, but have you actually read it? Read it aloud to yourself. Read it aloud to your team. Get feedback about whether you're describing the session accurately in the introduction for the participant. Tweak interview questions so they feel natural. Make sure that the task scenarios cover all the issues you want to explore. Draft follow-up questions.

- Dry run with a confederate. Pretending is not a good thing in a real session. But having someone act as your participant while you go through the script or protocol or checklist can give you initial feedback about whether the things you're saying and asking are understandable. It's the first indication of whether you'll get the data you are looking for.

- Rehearsal with a team member. Do a full rehearsal on all the parts. First, do a technical rehearsal. Does the prototype work? Do you know what you're doing in the recording software? Does the camera on the mobile sled hold together? If there will remote observers, make sure whatever feed you want to use will work for them by going through every step. When everything feels comfortable on the technical side, get a team member to be the participant and go through every word of the script. If you run into something that doesn't seem to be working, change it in the script right now.

- Pilot session with a real participant. This looks a lot like the rehearsal with the team member except for 3 things. First, the participant is not a team member, but a user or customer who was purposely selected for this session. Second, you will have refined the script after your experience of running a session using it with a team member. Third, you will now have been through the script at least 3 other times before this, so you should be comfortable with what the team is trying to learn and with the best way to ask about it. How many times have you run a usability test only to get to the 5th session and hear in your mind, 'huh, now I know what this test is about'? It happens.

All this rehearsal? As the moderator of a research session, you're not the star -- the participant is. But if you aren't comfortable with what you're doing and how you're doing it, the participant won't be comfortable and relaxed. either. And you won't get the most out of the session. But after you get into the habit of rehearsing, when it comes game time, you can concentrate on what is happening with the participant. Instead, those rehearsal steps become ways to test the test, rather than testing you.

There's a lot of truth to "practice makes perfect." When it comes to conducting user research sessions, that practice can make all the difference in getting valid data and useful insights. As Yogi Bera said, "In theory, there's no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is."

Friday, May 18, 2012

Wilder than testing in the wild: usability testing by flash mob

It was a spectacularly beautiful Saturday in San Francisco. Exactly the perfect day to do some field usability testing. But this was no ordinary field usability test. Sure, there’d been plenty of planning and organizing ahead of time. And there would be data analysis afterward. What made this test different from most usability tests?

Ever heard of Improv Everywhere? This was the UX equivalent. Researchers just appeared out of the crowd to ask people to try out a couple of designs and then talk about their experiences. Most of the interactions with participants were about 20 minutes long. That’s it. But by the time the sun was over the yardarm (time for cocktails, that is), we had data on two designs from 40 participants. The day was amazingly energizing.

How the day worked

The timeline for the day looked something like this:

8:00

Coordinator checks all the packets of materials and supplies

10:00

Coordinator meets up with all the researchers for a briefing

10:30

Teams head to their assigned locations, discuss who should lead, take notes, and intercept

11:00

Most teams reach their locations, check in with contacts (if there are contacts), set up

11:15-ish

Intercept the first participants and start gathering data

Break when needed

14:00

Finish up collecting data, head back to the meeting spot

14:30

Teams start arriving at the meeting spot with data organized in packets

15:00-17:00

Everybody debriefs about their experiences, observations

17:00

Researchers head home, energized about what they’ve learned

Later

Researchers upload audio and video recordings to an online storage space

On average, teams came back with data from 6 or 7 participants. Not bad for a 3-hour stretch of doing sessions.

The role of the coordinator

I was excited about the possibilities, about getting a chance to work with some old friends, and to expose a whole bunch of people to a set of design problems they had not been aware of before. If you have thought about getting everyone on your team to do usability testing and user research, but have been afraid of what might happen if you’re not with them, conducting a study by flash mob will certainly test your resolve. It will be a

lesson in letting go.

There was no way I could join a team for this study. I was too busy coordinating. And I wanted to be available in case there was some kind of emergency. (In fact, one team left the briefing without copies of the thing they were testing. So I jumped in a car to deliver to them.)

Though you might think that the 3-or-so hours of data collection might be dull and boring for the coordinator, there were all kinds of things for me to do: resolve issues with locations, answer questions about possible participants, reconfigure teams when people had to leave early. Cell phones were probably the most important tool of the day.

I had to believe that the planning and organizing I had done up front would work for people who were not me. And I had to trust that all the wonderful people who showed up to be the flash mob were as keen on making this work as I was. (They were.)

Keys to making flash mob testing work

I am still astonished that a bunch of people would show up on a Saturday morning to conduct a usability study in the street without much preparation. If your team is half as excited about the designs you are working on as this team was, taking a field trip to do a flash mob usability test should be a great experience. That is the most important ingredient to making a flash mob test work: people to do research who are engaged with the project, and enthusiastic about getting feedback from users.

Contrary to what you might think, coordinating a “flash” test doesn’t happen out of thin air, or a bunch of friends declaring, “Let’s put on a show!” Here are 10 things that made the day work really well to give us quick and dirty data:

1. Organize up front

2. Streamline data collection

3. Test the data collection forms

4. Minimize scripting

5. Brief everyone on test goals, dos and don’ts

6. Practice intercepting

7. Do an inventory check before spreading out

8. Be flexible

9. Check in

10. Reconvene the same day

Introduce all the researchers ahead of time, by email. Make the materials available to everyone to review or at least peek at as soon as possible. Nudge everyone to look at the stuff ahead of time, just to prepare.

Put together everything you could possibly need on The Day in a kit. I used a small roll-aboard suitcase to hold everything. Here’s my list:

About 10 days ahead, I chose a lead for each of the teams (these were all people who I knew were experienced user researchers) and talked with them. I put all the stuff listed above in a large, durable envelope with the team lead’s name on it.

The data collection form was the main thing I spent time on in the briefing before everyone went off to collect data. There are things I will emphasize more, next time, but overall, this worked pretty well. One note: It is quite difficult to collect qualitative data in the wild by writing things down. Better to audio record.

The other tip here is to write out the exact wording for the session (with primary and follow up questions), and threaten the researchers with being flogged with a wet noodle if they don’t follow the script.

I also handed cash that the researchers could use for transit or parking or lunch, or just keep.

Wilder than testing in the wild, but trust that it will work

On that Saturday in San Francisco the amazing happened: 16 people who were strangers to one another came together to learn from 40 users about how well a design worked for them. The researchers came out from behind their monitors and out of their labs to gather data in the wild. The planning and organizing that I did ahead of time let it feel like a flash mob event to the researchers, and it gave them room to improvise as long as they collected valid data. And it worked. (See the results.)

P.S. I did not originate this approach to usability testing. As far as I know, the first person to do it was Whitney Quesenbery in New York City in the autumn of 2010.

- 16 people gathered to make 6 research teams

- Most of the people on the teams had never met

- Some of the research teams had people who had never taken part in usability

testing before - The teams were going to intercept people on the street, at libraries, in farmers’

- markets

Ever heard of Improv Everywhere? This was the UX equivalent. Researchers just appeared out of the crowd to ask people to try out a couple of designs and then talk about their experiences. Most of the interactions with participants were about 20 minutes long. That’s it. But by the time the sun was over the yardarm (time for cocktails, that is), we had data on two designs from 40 participants. The day was amazingly energizing.

How the day worked

The timeline for the day looked something like this:

8:00

Coordinator checks all the packets of materials and supplies

10:00

Coordinator meets up with all the researchers for a briefing

10:30

Teams head to their assigned locations, discuss who should lead, take notes, and intercept

11:00

Most teams reach their locations, check in with contacts (if there are contacts), set up

11:15-ish

Intercept the first participants and start gathering data

Break when needed

14:00

Finish up collecting data, head back to the meeting spot

14:30

Teams start arriving at the meeting spot with data organized in packets

15:00-17:00

Everybody debriefs about their experiences, observations

17:00

Researchers head home, energized about what they’ve learned

Later

Researchers upload audio and video recordings to an online storage space

On average, teams came back with data from 6 or 7 participants. Not bad for a 3-hour stretch of doing sessions.

The role of the coordinator

I was excited about the possibilities, about getting a chance to work with some old friends, and to expose a whole bunch of people to a set of design problems they had not been aware of before. If you have thought about getting everyone on your team to do usability testing and user research, but have been afraid of what might happen if you’re not with them, conducting a study by flash mob will certainly test your resolve. It will be a

lesson in letting go.

There was no way I could join a team for this study. I was too busy coordinating. And I wanted to be available in case there was some kind of emergency. (In fact, one team left the briefing without copies of the thing they were testing. So I jumped in a car to deliver to them.)

Though you might think that the 3-or-so hours of data collection might be dull and boring for the coordinator, there were all kinds of things for me to do: resolve issues with locations, answer questions about possible participants, reconfigure teams when people had to leave early. Cell phones were probably the most important tool of the day.

I had to believe that the planning and organizing I had done up front would work for people who were not me. And I had to trust that all the wonderful people who showed up to be the flash mob were as keen on making this work as I was. (They were.)

Keys to making flash mob testing work

I am still astonished that a bunch of people would show up on a Saturday morning to conduct a usability study in the street without much preparation. If your team is half as excited about the designs you are working on as this team was, taking a field trip to do a flash mob usability test should be a great experience. That is the most important ingredient to making a flash mob test work: people to do research who are engaged with the project, and enthusiastic about getting feedback from users.

Contrary to what you might think, coordinating a “flash” test doesn’t happen out of thin air, or a bunch of friends declaring, “Let’s put on a show!” Here are 10 things that made the day work really well to give us quick and dirty data:

1. Organize up front

2. Streamline data collection

3. Test the data collection forms

4. Minimize scripting

5. Brief everyone on test goals, dos and don’ts

6. Practice intercepting

7. Do an inventory check before spreading out

8. Be flexible

9. Check in

10. Reconvene the same day

Organize up front

Starting about 3 or 4 weeks ahead of time, pick the research questions, put together what needs to be tested, create the necessary materials, choose a date and locations, and recruit researchers.Introduce all the researchers ahead of time, by email. Make the materials available to everyone to review or at least peek at as soon as possible. Nudge everyone to look at the stuff ahead of time, just to prepare.

Put together everything you could possibly need on The Day in a kit. I used a small roll-aboard suitcase to hold everything. Here’s my list:

- Pens (lots of them)

- Clipboards, one for each team

- Flip cameras (people took them but did most of the recording on their phones)

- Scripts (half a page)

- Data collecting forms (the other half of the page)

- Printouts of the designs, or device-accessible prototypes to test

- Lists of names and phone numbers for researchers and me

- Lists of locations, including addresses, contact names, parking locations, and public transit routes

- Signs to post at locations about the study

- Masking tape

- Badges for each team member – either company IDs, or nice printed pages with the first names and “Researcher” printed large

- A large, empty envelope

About 10 days ahead, I chose a lead for each of the teams (these were all people who I knew were experienced user researchers) and talked with them. I put all the stuff listed above in a large, durable envelope with the team lead’s name on it.

Streamline data collection

The sessions were going to be short, and the note-taking awkward because of doing this research in ad hoc places, so I wanted to make data collection as easy as possible. Working from a form I borrowed from Whitney Quesenbery, I made something that I hoped would be quick and easy to fill in and easy for me to understand what the data meant later. |

| Data collector for our flash mob usability test |

The data collection form was the main thing I spent time on in the briefing before everyone went off to collect data. There are things I will emphasize more, next time, but overall, this worked pretty well. One note: It is quite difficult to collect qualitative data in the wild by writing things down. Better to audio record.

Test the data collection forms

While the form was reasonably successful, there were some parts of it that didn’t work that well. Though a version of the form had been used in other studies before, I didn’t ask enough questions about the success or failure of the open text (qualitative data) part of the form. I wanted that data desperately, but it came back pretty messy. Testing the data collection form with someone else would have told me what questions researchers would have about that (meta, no?), and I could have done something else. Next time.Minimize scripting

Maximize participant time by dedicating as much time to the session as possible to their interacting with the design. That means that the moderator does nothing to introduce the session, instead relying on an informed consent form that one of the team members can administer to the next participant while the current one is finishing up.The other tip here is to write out the exact wording for the session (with primary and follow up questions), and threaten the researchers with being flogged with a wet noodle if they don’t follow the script.

Brief everyone on test goals, dos and don’ts

All the researchers and I met up at 10am and had a stand-up meeting in which I thanked everyone profusely for joining me in the study. And then I talked about and took questions on:- The main thing I wanted to get out of each session. (There was one key concept that we wanted to know whether people understood from the design.)

- How to use the data collection forms. (We walked through every field.)

- How to use the script. (“You must follow the script.”)

- How to intercept people, inviting them to participate. (More on this below.)

- Rules about recordings. (Only hands and voices, no faces.)

- When to check in with me. (When you arrive at your location; at the top of each hour, when you’re on the way back.)

- When and where to meet when they were done.

I also handed cash that the researchers could use for transit or parking or lunch, or just keep.

Practice intercepting people

Intercepting people to participate is the hardest part. You walk up to a stranger on the street asking them for a favor. This might not be bad in your town. But in San Francisco, there’s no shortage of competition. Homeless people, political parities registering voters, hucksters, buskers, and kids working for Greenpeace all wanting attention from passers-by. And there you are, trying to do a research study. So, how to get some attention without freaking people out? A few things that worked well:- Put the youngest and/or best-looking person on the task.

- Smile and make eye contact.

- Using cute pets to attract people. Two researchers who own golden retrievers brought their lovely dogs with them, which was a nice icebreaker.

- Start off with what you’re not: “I’m not selling anything, and I don’t work for Greenpeace. I’m doing a research study.”

- Start by asking for what you want: “Would you have a few minutes to help us make ballots easier to use?”

- Take turns – it can be exhausting enduring rejection.

Do an inventory check before spreading out

Before the researchers went off to their assigned locations, I asked each team to check that they had everything they needed, which apparently was not thorough enough for one of my teams. Next time, I will ask each team to empty out the contents of the packet and check the contents. I’ll use the list of things I wanted to include in each team’s packet and my agenda items for the briefing to ask the teams to look for each item.Be flexible

Even with lots of planning and organizing, things happen that you couldn’t have anticipated. Researchers don’t show up, or their schedules have shifted. Locations turn out to not be so perfect. Give teams permission to do whatever they think is the right thing to get the data – short of breaking the law.Check in

Teams checked in when they found their location, between sessions, and when they were on their way back to the meeting spot. I wanted to know that they weren’t lost, that everything was okay, and that they were finding people to take part. Asking teams to check in also gave them permission to ask me questions or help them make decisions so they could get the best data, or tell me what they were doing that was different from the plan. Basically, it was one giant exercise in The Doctrine of No Surprise.Reconvene the same day

I needed to get the data from the research teams at some point. Why not meet up again and share experiences? Turns out that the stories from each team were important to all the other teams, and extremely helpful to me. They talked about the participants they’d had and the issues participants ran into with the designs we were testing. They also talked about their experiences with testing this way, which they all seemed to love. Afterward, I got emails from at least half the group volunteering to do it again. They had all had an adventure, met a lot of new people, got some practice with skills, and helped the world be a become a better place through design.Wilder than testing in the wild, but trust that it will work

On that Saturday in San Francisco the amazing happened: 16 people who were strangers to one another came together to learn from 40 users about how well a design worked for them. The researchers came out from behind their monitors and out of their labs to gather data in the wild. The planning and organizing that I did ahead of time let it feel like a flash mob event to the researchers, and it gave them room to improvise as long as they collected valid data. And it worked. (See the results.)

P.S. I did not originate this approach to usability testing. As far as I know, the first person to do it was Whitney Quesenbery in New York City in the autumn of 2010.

Labels:

collecting data,

field testing,

flash mob,

flashmob,

intercepting,

tips,

usability testing

Saturday, May 12, 2012

Are you testing for delight?

Everybody's talking about designing for delight. Even me! Well, it does get a bit sad when you spend too much time finding bad things in design. So, I went positive. I looked at positive psychology, and behavioral economics, and the science of play, and hedonics, and a whole bunch of other things, and came away from all that with a framework in mind for what I call "happy design." It comes in three flavors: pleasure, flow, and meaning.

I used to think of the framework as being in layers or levels. But it's not like that when you start looking at great digital designs and the great experiences they are part of. Pleasure, flow and meaning end up commingled.

So, I think we need to deconstruct what we mean by "delight." I've tried to do that in a talk that I've been giving, most recently at RefreshPDX (April 2012). Here are the slides. Have a look:

I used to think of the framework as being in layers or levels. But it's not like that when you start looking at great digital designs and the great experiences they are part of. Pleasure, flow and meaning end up commingled.

So, I think we need to deconstruct what we mean by "delight." I've tried to do that in a talk that I've been giving, most recently at RefreshPDX (April 2012). Here are the slides. Have a look:

Labels:

delight,

flow,

happy design,

meaning,

ommwriter,

pleasure,

positive psychology,

virgin america,

zipcar

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

Persona Modeler: a framework for essential persona attributes

Strictly speaking, personas have nothing to do with usability testing. But personas can fill in as users when we're designing, and some teams recruit for studies using attributes of personas they've developed. Connection? I think so.

The Persona Modeler (earlier called "character creator") is a tool that I've been working with and refining for several years to help me define and understand users. I gave a talk about how it works at UPA Boston 2012. Here are the slides. Feel free to download!

The Persona Modeler (earlier called "character creator") is a tool that I've been working with and refining for several years to help me define and understand users. I gave a talk about how it works at UPA Boston 2012. Here are the slides. Feel free to download!

Labels:

ability,

accessibility,

aptitude,

attitude,

behavior,

demographics,

emotion,

model,

persona,

persona modeler,

profile,

skill,

users

Wednesday, March 7, 2012

The form that changed *everything*

If this post rocks your world in any small way, please consider backing my Kickstarter. It's called Field Guides To Ensuring Voter Intent.

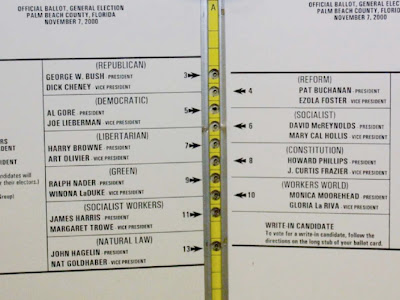

It worked until a well-intentioned public servant, who

wanted to help her overwhelmingly older voters read and use the ballot, decided

to make the type larger than this ballot normally allowed. In proper use of this ballot template,

all the candidates are lined up on the left side of the spread. But increasing

the type size flowed the candidates for president onto two pages, creating an

interlaced effect. This made the choices difficult to line up properly.

World peace through design: Lessons from crises

Now, there ARE amazing, excellent things going on in design that are changing the world in excitingly good ways. Many of those good things are happening in election design. Unfortunately, most of these are in response to crises. But never mind. The point is, we're at the cusp of a movement in design for good, moving toward a future of world peace through design. Let me show you just a few examples.

There's a lot of crap going on in the world right now:

terrorism, two major wars, and worldwide economic collapse. Let’s not forget

the lack of movement on climate change and serious unrest in the Middle East

and other places.

People trust governments less than ever -- perhaps because

of the transparency that ambient technology brings -- leading to more

regulation of privacy and security, but also to protests. Protests that started

in Egypt have rippled around the world.

This wave started with a butterfly. Not the butterfly of

chaos theory, but there is a metaphor here that should not be missed: when a

butterfly flaps its wings in the Amazon rainforest, there are ripple effects that

you might not realize. The butterfly I am talking about is the butterfly ballot

used in Palm Beach County, Florida in the US 2000 presidential election.

|

| Palm Beach County, Florida November 2000 ballot |

Design affects world peace

A ballot is a form. A form used in one of the most important

interactions between a government and its citizens. This particular form

changed everything.

This ballot, like every government form, is the culmination

of a set of design decisions that were well intentioned, but also took

constraints into account.

The way the voting system in Palm Beach County worked – it

is no longer in use there -- is that there is a little booklet mounted on a

slot that a card fits in. The spine of each double page spread has a series of

holes down it. The voter finds the candidate she wants to vote for, and presses

a point through the hole to push a perforated box out of the card in the slot

behind the little book. When

you’re finished voting, you slide the card out from behind the book and drop it

into a ballot box. At the end of Election Day, the cards are run through a computer

to tabulate the votes. This is a computing technology from the 1960s, but for a

voting system, it worked fine for a very long time.

|

| A punchcard ballot system from Los Angeles County |

|

Vote for Republican candidates by punching the first hole.

Vote for Democrats by punching... which?

|

If you wanted to vote for Al Gore and Joe Lieberman, which

hole do you punch? Thousands of voters thought it was the second one. It

wasn't. Punching that hole casts a vote for Pat Buchanan. Pat Buchanan is an

ultra conservative, Christian fundamentalist, and a very unlikely choice for the

many liberal, retired people who lived in Palm Beach County, Florida.

|

| Vote for Reform party candidates by punching the second hole |

While the design decision seemed like the right one because

it took users into account, it was done without data, without testing the new

design for its usability, by someone trained and practiced in public

administration, but not in design.

World peace through design: Lessons from crises

Now, there ARE amazing, excellent things going on in design that are changing the world in excitingly good ways. Many of those good things are happening in election design. Unfortunately, most of these are in response to crises. But never mind. The point is, we're at the cusp of a movement in design for good, moving toward a future of world peace through design. Let me show you just a few examples.

After a contested election in Minnesota for a seat in the US

Senate that Al Franken eventually won by just a few hundred votes, the official

in charge of elections in that state decided to usability test and redesign absentee

ballots there. She loved what she learned from the process so much after

working on absentee ballots that her team went on to work on other important

forms, such as voter registration forms.

In New York State, after being sued for usability problems

with the new vote tabulating systems, the board of elections conducted

usability tests on three prototyped messages. With the assistance of the voting system manufacturers, the

board and a few advisors came up with messages and designs that will work on two different voting systems, within state laws,

across 62 counties. The board of elections staff has also received basic

training in user research, ballot design, plain language, and usability

testing.

At the federal level, one response to the mortgage meltdown

was to form the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau.

Its first task was to rewrite and redesign disclosures given to borrowers to

make them easier to read, understand, and act on. Before the mortgage crisis, borrowers

didn’t understand the consequences of borrowing the types of loans they were

borrowing. Design will now make a difference for both lenders and borrowers.

The thing is, design in civic life, and I would call all of

these examples from civic life, is good for business. When the business of

government includes design as a priority, costs of development and support are

lower than when design is not consciously, actively part of the process of

delivery to citizens. And business benefits from good design in civic life

because it keeps regulation and costs down for suppliers. Unintended negative

outcomes are much less likely when design decisions are informed by data.

Simple usability tests could have prevented people voting counter to their

intentions. Simple usability tests could have prevented borrowers from making

decisions counter to their best interests.

Don't let it happen again

Don't let it happen again

We’ve seen what well intentioned but poor design decisions

can do. (The product manager who tweaks something at the last minute?) There

are some gaps in what we know about ballot design that could make the

difference for thousands of voters in the next national election. Let’s learn

how to design for those gaps and help local election officials make good design

decisions. If you do user research and usability testing as part of your job, I

encourage you to volunteer in your local election department to proofread

ballots and other voter-facing materials, or be a poll worker, or both.

Don’t let the butterfly ballot happen again.

If this post rocks your world in any small way, please consider backing my Kickstarter. It's called Field Guides To Ensuring Voter Intent.

Thursday, January 5, 2012

Four secrets of getting great participants who show up

What if you had a near-perfect participant show rate for all your studies? The first time it happens, it’s surprising. The next few times, it’s refreshing -- a relief. Teams that do great user research start with the recruiting process, and they come to expect near perfect attendance.

Secret 1: Participants are people, not data points

The people who opt in to a study have rich, complex lives that offer rich, complex experiences that a design may or may not fit into. People don’t always fit nicely into the boxes that screening questionnaires create.

Screeners can be constraining not in a good way. An agency that isn’t familiar with your design or your audience or both -- and may not be experienced with user research -- may eliminate people who could be great in user research or usability testing. Teams we work with find that participants who are selected through open-ended interviews conducted voice-to-voice become engaged and invested in the study. The conversation helps the participant know they’re interesting to you, and that makes them feel wanted. The team learns about variations in the user profile that they might want to design for.

Secret 2: Participants are in the network

Let’s say the source is panel or a database (versus a customer list). People who sign up to be in panels or recruiting databases tend to be people who take part in studies to make easy money. Many are the kind of people who fill out surveys to win prizes. These people might be good participants, or they might not.

Teams that find study participants through personal, professional, and community networks find that when the network snowball of connections works, people respond because they’re interested and have something to offer (or a problem you might solve for them with your design).

They also come partially pre-screened. Generally, your friends of friends of friends don’t want to embarrass the people who referred them. If the call for participants is clear and compelling, the community coordinator at the church, school, club, union, or team will remember to mention the study as soon as they encounter someone they know who might fit. Don’t worry: the connections soon get far enough away from you and your direct network that your data will be just as objective and clean as can be.

Secret 3: Participants want to help you

They want to be picked for your team. They want to share their experiences and demonstrate their expertise. When teams are open to the wide range of participants’ experiences, they learn from participants during screening. Those selected become engaged in the research. These are participants who call when they’re going to be late, or apologize for having to switch times. They want to work with you. One team we worked with had a participant call from a car accident before calling the police. (They rescheduled!)

Secret 4: Participants need attention

You know all the details that go into a study. Participants need confirmation and reminding. Teams that send detailed email confirmations get respectable show rates. Teams that send email confirmations, and then email reminders just before the sessions get good show rates. Teams that send email confirmations, email reminders, and then call the participants to remind them in a friendly, inviting tone get stellar show rates.

Some teams use the call before the session to start the “official” research. Rather than the recruiter doing the final call, the researcher phones to explain the study and the roles, and ask some of the warm up questions you might normally start a regular session with. These researchers establish a relationship with the participant. They also get a head start, leaving more time when they’re face-to-face with a participant to observe behavior rather than interview.

Perfect attendance is worth the effort

When all the scheduled participants show up, the gold stars come not only for efficient use of the time in the lab and keeping clients and team members eyes and ears with users. It’s likely the team ends up with better, more appropriate, more informative participants, overall. That means better, more reliable data to inform design decisions.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)